Ron Berger —

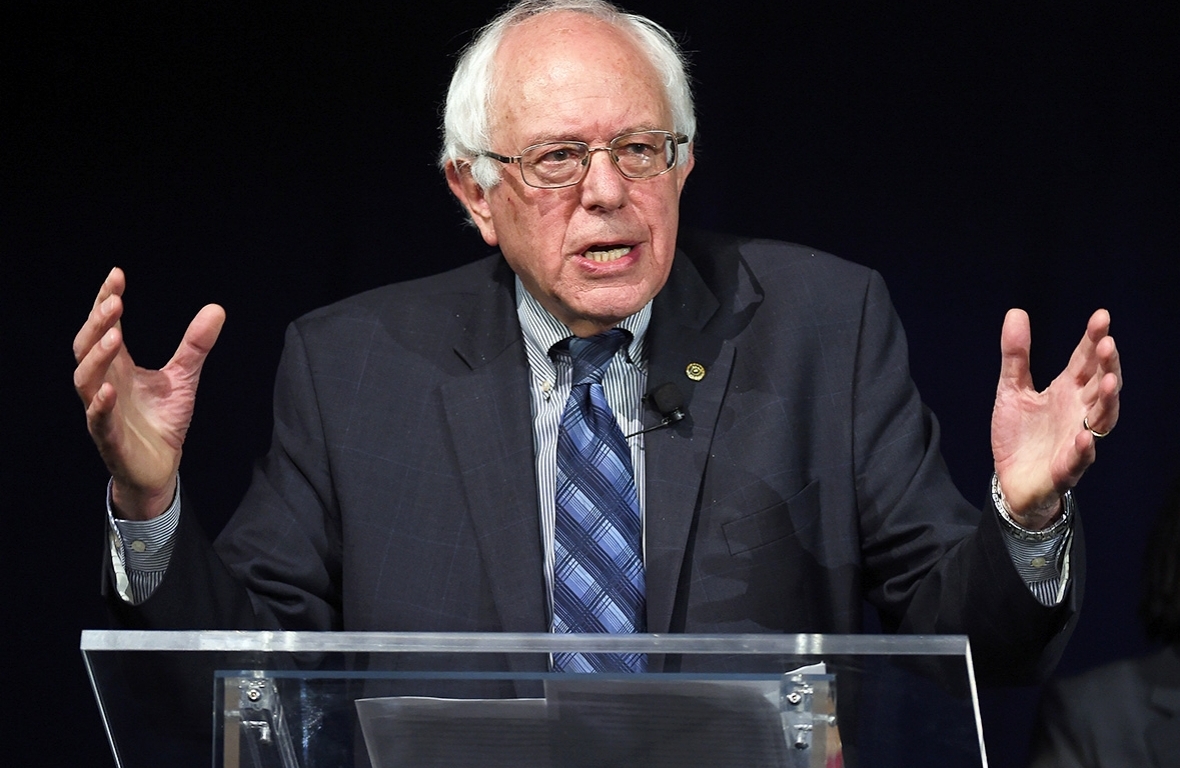

Bernie Sanders has not become the Democratic nominee for president in 2016, but he has left an indelible mark on political campaign history. For one, no other presidential candidate since Eugene Debs in the early 1900s has raised socialism as a legitimate political issue, dismissed by Hillary Clinton more for its idealism and impracticality than its association with communism. Second, Sanders has forced Clinton to take policy positions to the left of what she would have taken if not for his candidacy, even causing her to adopt (verbatim at times) his campaign rhetoric. And the policy issues and political constituency Sanders represents will likely remain a powerful force within the Democratic Party for the foreseeable future.

Bernie Sanders has not become the Democratic nominee for president in 2016, but he has left an indelible mark on political campaign history. For one, no other presidential candidate since Eugene Debs in the early 1900s has raised socialism as a legitimate political issue, dismissed by Hillary Clinton more for its idealism and impracticality than its association with communism. Second, Sanders has forced Clinton to take policy positions to the left of what she would have taken if not for his candidacy, even causing her to adopt (verbatim at times) his campaign rhetoric. And the policy issues and political constituency Sanders represents will likely remain a powerful force within the Democratic Party for the foreseeable future.

But there is another element of Sanders’s candidacy that has only tangentially generated discussion that is worthy of further consideration: What it says about the politics of Jewish Americans in the United States. It is this issue that I address in this article.

Sanders was born in Brooklyn in 1941, the son of a Yiddish-speaking traveling paint salesman who had immigrated from Poland and lost most of his family in the Holocaust and of a first-generation Jewish homemaker who suffered from rheumatic fever and died during a heart operation when Sanders was 17 years old. As a youth Sanders attended Hebrew school and was bar mitzvahed, and in his early twenties he spent some time on an Israeli kibbutz.

This is a background, however, that Sanders is reluctant to talk about. When asked about his religious beliefs, he says he is proud of his Jewish heritage, but he is more likely to refer to his father as a Polish (not Jewish) immigrant. He does describe his social justice values as having “spiritual” roots, but there is no mistaking the fact, as he says, that he is “not particularly religious.” He will tell listeners that part of his family was killed by the Nazis, but in doing so he invokes the moral gravitas of a man who understands suffering and not as a man who believes in God.

Unlike former Senator Joe Lieberman, who was Al Gore’s vice-presidential running mate in 2000, the Jewish-American community does not view Sanders as one of their own. Lieberman is a devout Jew who talks openly about his faith. Sanders, in contrast, is more likely to invoke the moral authority of Pope Francis than the God of the Hebrews; and he has been more critical of the Israeli government’s policies vis-à-vis the Palestinian people than any presidential candidate on either side of the aisle.

Be that as it may, Sanders has already made Jewish-American history. Whereas Lieberman was the first Jew to be part of a presidential ticket, Sanders is the first to have ever won a state-level primary contest; and he won twenty-two overall, garnering 46 percent of the pledged delegates to the 2016 Democratic Party convention. But it is one thing to note that Sanders is the first Jew to do one thing or another, it is quite another to embed his accomplishments in broader context. Doing so will require some historical background.

The Origins of the Jewish Question

Throughout history, Jews have lived in Christian-dominated countries feeling what W. E. DuBois famously observed of black people in America: “How does it feel to be a problem?” In Europe, especially in Germany, this problem was referred to as the “Jewish Question.” According to historian Paul Rose, German discourse on the Jewish Question revolved around the meaning of Judentum, which contained three interrelated meanings when rendered in English: (1) Judaism as a religion, (2) Jewry as a community or nation of people, and (3) Jewishness as a quality adhering to Jews and Judaism.

Throughout history, Jews have lived in Christian-dominated countries feeling what W. E. DuBois famously observed of black people in America: “How does it feel to be a problem?” In Europe, especially in Germany, this problem was referred to as the “Jewish Question.” According to historian Paul Rose, German discourse on the Jewish Question revolved around the meaning of Judentum, which contained three interrelated meanings when rendered in English: (1) Judaism as a religion, (2) Jewry as a community or nation of people, and (3) Jewishness as a quality adhering to Jews and Judaism.

The pariah social status of European Jews arguably originates with Christian anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism is a relatively modern term; its introduction into popular usage is credited to the racist ideologue William Marr. In his book The Victory of Judaism over Germanism, published in the 1870s, Marr used the term to refer to different language-speaking groups—Aryan (Indo-European) and Semitic (Middle Eastern)—as separate races. Of the Jews Marr wrote, “I believe Judaism, because it is a racial particularity, is incompatible with our political and social life.” But before there was racial anti-Semitism, there was Christian anti-Semitism.

In the Christian-dominated countries of Europe, Jews were often reviled for their unwillingness to accept Jesus Christ as their lord and savior and Christianity as a religion that had supplanted Judaism. Insofar as Jews were well schooled in the Hebrew Bible and refused, in the words of sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, to accept Christianity “in full consciousness” of its meaning, “Christianity could not reproduce itself…without…explaining Jewish obstinacy by a malice aforethought, ill intentions and moral corruption.”

In this context, what emerged in Christian culture and was preached by Christian officials was a set of myths and accusations that held Jews responsible for a host of horrific acts. In addition to holding Jews (and not Roman authorities) almost exclusively responsible for Christ’s death, Jews were accused of engaging in “blood libel” (murdering Christian children to use their blood in religious rituals), desecrating the body of Christ (despoiling the Christian sacraments of bread and wine), poisoning wells, and spreading famines and plagues.

As a deprecated minority subject to prejudice and discrimination, European Jews were often forbidden from agricultural land ownership and hence excluded from a common source of livelihood. They thus sought economic survival in areas that complemented the majority population. In a world where commerce was poorly developed, people lacked literacy skills, and usury (money-lending for interest) was discouraged by Christian Scripture, Jews found a niche as merchants, bankers, physicians, and craftsmen. At the same time, their very success in these areas bred resentment, albeit resentment that did not necessarily emanate from actual experience or conflict with real people but from stereotypes that held Jews responsible for a multitude of local problems even though they were not causally related to any. In later years, this ubiquitous stereotype was used to blame Jews for the egregious excesses of both capitalism and socialism.

The Paradox of the Enlightenment

By the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, opened up new possibilities for European Jews. Enlightenment philosophy advanced the belief that humanity could rely on rational thought rather than religious authority to govern its affairs. By promoting democratic ideals and the separation of religion from politics and government, it fostered Jewish emancipation. But this was not the end of the story. On the one hand, traditional church officials and royalists who favored religious-based monarchies over secular democratic governments blamed Jews for fomenting unwanted social change. On the other hand, the architects of the Enlightenment expected Jews to relinquish their religious “superstitions” in order to become full citizens of the nation. They wanted to integrate Jews into the economy, as historian Arthur Hertzberg writes, “so that no particular pursuit, not even money lending, should be the Jew’s own preserve.” And they hoped to undermine the capacity of the organized Jewish community to advance any economic or political claims that were considered distinct from the broader national community.

In this way, Hertzberg argues, modern anti-Semitism “was fashioned not as a reaction to the Enlightenment” but as part of it. Whereas the more hostile Enlightenment thinkers thought that Jews were “by the very nature of their own culture and even by their biological inheritance an unassimilable element,” more sympathetic thinkers thought this inferior Jewish character was not due to their nature but to their circumstances or environment, and that if “Jews were given opportunity and freedom, they would change and very rapidly lose their bad habits.”

Karl Marx (1818-83) was one of the most notable heirs to this line of thinking, which is doubly ironic insofar as Marx was of German Jewish ancestry (his parents were Jewish but converted to Protestantism) and Bernie Sanders is an heir to the socialist tradition of which Marx played such an important part. In his essay “On the Jewish Question,” published in 1843, Marx appropriated the concept of Judentum to critique the obsessive materialism and egoism of capitalist society and the role of Jews in it. As he wrote:

Karl Marx (1818-83) was one of the most notable heirs to this line of thinking, which is doubly ironic insofar as Marx was of German Jewish ancestry (his parents were Jewish but converted to Protestantism) and Bernie Sanders is an heir to the socialist tradition of which Marx played such an important part. In his essay “On the Jewish Question,” published in 1843, Marx appropriated the concept of Judentum to critique the obsessive materialism and egoism of capitalist society and the role of Jews in it. As he wrote:

“The Jew has emancipated himself in a Jewish way, not only by acquiring financial power, but also because both through him and without him, money has become a world-power and the practical Jewish spirit has become the practical spirit of the Christian peoples….We therefore recognize in Judaism the presence of a universal and contemporary anti-social element whose historical evolution—eagerly nurtured by the Jews in its harmful aspects—has arrived at its present peak.”

According to Marx, revolutionary socialism was the solution to this state of affairs, but he was not the only socialist voice on the Jewish Question. Indeed, Moses Hess (1812-75), also known as the “communist rabbi,” the early founder of Zionism, and the man who helped convert Marx to socialism, reprimanded his good friend for “joining the German racist enemies of the Jews and insulting his ancestors to the grave.” For Hess, Zionism was the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, and the answer to the Jewish Question was not the disappearance of Jews as a nation but of their redemption into the dignity of nationhood. While Hess understood religion more generally as a potential source of human alienation, he saw in Judaism the possibilities of a “religion of love,” a revolutionary spirit that was seeking “a constitution worthy of the ancient mother.”

Jews in America

The Jewish presence in the United States goes back to colonial times, but the first major emigration from Europe spanned the period from the 1820s to the early 1920s. During that time many European Jews viewed America, not Palestine, as the proverbial “promised land,” what they called the Goldene Medina, or Golden State.

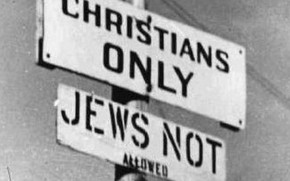

The Goldene Medina was not entirely hospitable to Jews, however. Anti-Semitism and institutional discrimination in business, government, higher education, and neighborhood covenants were commonplace. Moreover, in 1924 the National Origins Act (NOA) established limits on the number of people who were allowed to emigrate in any given year from any given country and was designed to favor those of Anglo-Saxon descent. Although the NOA did not formally target Jews, many of the bill’s proponents made negative comments about Jews in their effort to secure its passage. Later, in the midst of the Great Depression, further restrictions on immigration were enacted, and throughout the 1930s and World War II, Jews seeking refuge from Nazi persecution were denied a safe haven in the country.

The Goldene Medina was not entirely hospitable to Jews, however. Anti-Semitism and institutional discrimination in business, government, higher education, and neighborhood covenants were commonplace. Moreover, in 1924 the National Origins Act (NOA) established limits on the number of people who were allowed to emigrate in any given year from any given country and was designed to favor those of Anglo-Saxon descent. Although the NOA did not formally target Jews, many of the bill’s proponents made negative comments about Jews in their effort to secure its passage. Later, in the midst of the Great Depression, further restrictions on immigration were enacted, and throughout the 1930s and World War II, Jews seeking refuge from Nazi persecution were denied a safe haven in the country.

Prior to World War II, Judaism in the United States was embedded in an urban folk culture called Yiddishkeit—which translates generally as “Jewishness” or “Jewish essence”—that animated the segregated communities of that era. As a language, Yiddish goes back several centuries in Europe and provided a cultural link between Jews from different communities, regions, and nations. In the United States, Yiddishkeit created a common bond between religious and secular Jews and drew attention to elements of biblical Judaism derived from the ancient prophets that were compatible with a socialist vision of economic equality and social justice. According to anthropologist Karen Brodkin, “This does not mean that all Jews were socialists….It does mean that part of being Jewish was being familiar with a working-class and anticapitalist outlook…and understanding this outlook as being particularly Jewish.”

After World War II, as overt anti-Semitism diminished and subsequent generations of Jews became upwardly mobile, Jewish interest in socialism diminished. But Sanders is a reminder of this heritage, a heritage that harkens back to an earlier era in which some of the major figures in American socialism were immigrant Jews—Daniel De Leon (1852-1914), a leader of the Socialist Labor Party of America and a three-time unsuccessful candidate for New York governor; Victor Berger (1860-1929), founder of the Social Democratic Party of America and the man who converted Eugene Debs to socialism; and Morris Hillquit (1869-1933), co-founder of the Socialist Party of America. To these notables I would add Samuel Gompers (1850-1924), also an immigrant, the trade unionist who served as the first president of the American Federation of Labor; and Saul Alinsky (1909-72), the famed community organizer who was born in Chicago.

But it is not just Sanders’s political views but his cultural style that is germane to his Jewish connection. Writing in The New Republic, Joshua Cohen thinks, but is not sure he wants to defend, that he has “some understanding of what Jewishness means, or is signified by…Bernie Sanders.” By this he means that Sanders has some cultural resonance for him, and when Cohen writes that Sanders delivers his speeches with a Yiddish krechts, I interpret him as experiencing this cultural trait affectionately, a reminder of people he has known. Translated into English, krechts refers to a persistent complaint; in Sanders’s case, a complaint about money in politics, Wall Street greed, a rigged economy. Adorned by his besheveled white hair and glittering his speech with his trademark “yuge,” Sanders waves his hands and arms and rails, “Enough is enough!”

Cohen notes that when Larry David, also a Brooklyn Jew, plays Sanders on Saturday Night Live, he is in many ways mimicking himself, because the two of them are cut from the same cloth. “Larry David does not ‘do’ Bernie Sanders.” And neither do the other late-night comedians like Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Fallon, and Seth Meyers. “Instead, what they ‘do,’ and what they’re relishing ‘doing,’ is ‘Jew,’” and it surprises Cohen that no one has been willing to acknowledge this. “Jews know it, and none of them are offended, because Jews embrace Bernie for the same reason that everyone else does; they’re magnetized by one of the only things that America seems to lack: genuine political conviction, founded in an authentic ethnic identity that can be read as white, but that isn’t racist.”

Cohen notes that when Larry David, also a Brooklyn Jew, plays Sanders on Saturday Night Live, he is in many ways mimicking himself, because the two of them are cut from the same cloth. “Larry David does not ‘do’ Bernie Sanders.” And neither do the other late-night comedians like Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Fallon, and Seth Meyers. “Instead, what they ‘do,’ and what they’re relishing ‘doing,’ is ‘Jew,’” and it surprises Cohen that no one has been willing to acknowledge this. “Jews know it, and none of them are offended, because Jews embrace Bernie for the same reason that everyone else does; they’re magnetized by one of the only things that America seems to lack: genuine political conviction, founded in an authentic ethnic identity that can be read as white, but that isn’t racist.”

Sanders and the Black Vote

Jewish Americans have a noble history of involvement in the civil rights movement. Risking their lives alongside black protestors, for example, they accounted for nearly two-thirds of the white volunteers who went to Mississippi for the Freedom Summer voter registration drive in 1964. Overall, they remain among the most liberal consistencies of the American electorate, and a majority of them self-identify as members of or as sympathetic to the Democratic Party. It is only among Orthodox Jews, who comprise just 10 percent of Jews in the United States, that party affiliation tilts Republican.

Sanders, too, was involved in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After transferring to the University of Chicago from Brooklyn College in 1961, he joined the campus chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), protesting discrimination in university housing. During the time he served as chair, the university chapter of CORE merged with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and Sanders broadened the protests to include the Howard Johnson restaurant chain in the broader Chicago area. At one time he was arrested for protesting school segregation on the city’s South side.

Nonetheless, in the Democratic primary of 2016, Sanders did poorly among black voters. Overall, Hillary Clinton received more than 70 percent of the black vote; and among black voters 45 years and older, she received 85 to 90 percent. Only among black voters younger than 30 years of age, who vote in lower numbers than their older counterparts, did Sanders narrowly win the vote. In my view, Sanders’s inability to attract black voters is the single most important reason he did not win the Democratic Party nomination for president.

The reasons for Sanders’s poor showing among black voters are complex. For one, Bill Clinton remains popular among this consistency, in spite of the pro-incarceration policies and so-called welfare reform he enacted in the 1990s. Kevin Alexander Gray observes that black voters “are sticking with the devil they know,” and Michael Eric Dyson notes that “black folk are done with symbolic candidates. Despite the appeal of…Sanders’s economic platform, and his growing sensitivity to race,…they want no part of him.”

Additionally, Sanders has done little during his three decades in Congress to cultivate meaningful ties to black politicians, and his claim to “authenticity” does not resonate with them. Hence there was the remark of civil rights icon John Lewis, on the occasion of the Congressional Black Caucus’s endorsement of Hillary Clinton, when Lewis took a dig at Sanders by saying that he had never encountered Sanders, but had encountered the Clintons, during his work in the 1960s.

Moreover, Sanders’s criticism of Obama has not sat well among many black voters, especially black women. Writing of his home state of South Carolina, Gray notes that “Women are 60 percent of the black electorate…and you are hard pressed to find a black voter who does not feel strongly supportive of the first black president.” Although Hillary Clinton started her campaign by saying she is not running for a third Obama term, she quickly learned that embracing Obama was key to winning the Democratic primary.

There is also the matter of Sanders’s cultural style. Early in the campaign, Joan Walsh reported on a rally in which “Sanders wondered out loud why he gets so much support from young voters, [and] a fired-up black female supporter shouted admiringly: ‘You’re like a grandpa! You’re like a grandpa!’ The crowd laughed and clapped, but Sanders didn’t reply. She stepped it up. ‘Be my grandpa!’ Sanders just went on with his speech. He doesn’t do call-and-response….At the end, he got warm but not overwhelming applause.” And Gray reminds us of the incident when Sanders arrived late to a lunch event at a Baptist church and was given a lukewarm reception. Unlike both the Clintons and Obama, Sanders is not at home in a church environment, and church-going audiences know this.

Conclusion

Earlier I noted that Jewish Americans remain one of the most liberal political constituencies in the United States. In part, this inclination stems from their historic marginal status and ongoing appreciation of the need to separate religion from politics and government. Moreover, it has been Democratic presidents who most advanced Jewish entrance into the higher echelons of the U.S. government. It was President Woodrow Wilson, for example, who appointed Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish justice to the U.S. Supreme Court; and it was President Franklin Roosevelt who allowed an unprecedented number of Jews into his administration. Currently as well, Christian evangelicals’ repeated references to the United States as being (or needing to be) a “Christian nation,” and the intended or unintended marginalization of non-Christian minorities (especially Muslims) that this entails, chastens Jews against joining the political coalition that has been built by the Republican Party.

More germane to the Jewish Question, however, is Joshua Cohen’s observation that Sanders’s critique of moneyed interests brushes up against the historic stereotype of Jews as the denizens of finance capitalism. Although Jews comprise just 2 percent of the U.S. population, they comprise more than 40 percent of U.S. billionaires. Unlike Cohen, Sanders does not speak of such matters; he is no Karl Marx and may not even think such thoughts. But what is truly remarkable about Sanders, Cohen thinks, is that a Brooklyn Jew whose life took him to Vermont could convince a state full of libertarian gun-owners that he was as much like them to elect him as mayor of the state’s largest city, send him to Congress, and almost the presidency of the United States.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Charles Cottle and Jeff Berger for their input on this article.

Sources

Zygmunt Bauman. 1989. Modernity and the Holocaust. Cornell University Press.

Russell Berman. 2016. “Bernie Sanders Bids for Jewish History.” The Atlantic (Jan. 27).

Karen Brodkin. 1998. How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says about Race in America. Rutgers University Press.

Joshua Cohen. 2016. “Bernie’s Complaint: The Reluctant Roots of Radicalism.” The New Republic (Apr. 16).

Michael Eric Dyson. 2015. “Yes She Can: Why Hillary Clinton Will Do More for Black People than Obama.” The New Republic (Nov. 29).

Kevin Alexander Gray. 2016. “Why Black Voters Aren’t Feeling the Bern.” The Progressive (Mar. 2).

Arthur Hertzberg. 1968. The French Enlightenment and the Jews: The Origins of Modern Anti-Semitism. Shocken.

Paul Lawrence Rose. 1990. Revolutionary Antisemitism in Germany: From Kant to Wagner. Princeton University Press.

Joan Walsh. 2015. “Are Black Women Ready for Hillary?” The Nation (Nov. 24).

I’m so glad you wrote this–it’s an angle that I’ve seen very little of in the millions of words of commentary on the presidential race this year.

LikeLike

Thank you, Karen. Glad you found it of interest.

LikeLike

Thanks Ron- You just stuffed an entire hemisphere of information into my brain/head. Thanks too for providing enough thought for a new perspective, though I’ve only recently dismissed Woodrow Wilson as an elitist racist. But that doesn’t detract from your construct… you’ll have me lying awake at night- “cogitatin”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ron this is a very impressive work of scholarship and insight into the Democratic race for president. I’ll admit I’m not a big fan of Bernie, nor of Hillary, as I’d just as soon vote for Obama for a third term, but I understand that may not be possible. I appreciate reading about Sanders’s background, and how that background fits into a larger picture of Jewish life reflected in modern politics. I’m convinced big money will always contribute to the presidential races, as well as probably all of the other national and state races, which is disappointing as sooner or later, one has to recognize that nearly all politicians owe huge debts to lobbyists and superpac donors. Thanks for this article, and I hope it’s picked up in journals such as The Progressive in Madison….have you submitted it for review elsewhere? One short writer’s question, from start to finish, can you estimate the time for drafting and editing your article….it seems like it might have taken a few months to work on, but now it is a fine piece of scholarship.

LikeLike

Thanks DeWitt. It really didn’t take that long to write, because the topic is within the parameters of my previous work and areas of interest. Currently I don’t have plans to re-publish it anywhere else, but I do hope that you and others will share it with your friends (including Facebook friends).

LikeLike

Ron, this is my first comment since being invited to join this august group and I’ve very happy to be here and to have read your article.

It is wonderful. It highlights for me the difficulty of being a politician in an enormous multicultural environment. I’m a Sanders fan and have gotten the “persistent complaint” aspect of his Jewishness which I don’t find off-putting at all. But, as a Baptist in the South, I think I might be put off if he appeared to be uncomfortable in my church. I might understand it, but I also might be put off.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Welcome to Wise Guys, Ellin. Thank you for your comments. We are glad to have you on board with our project.

LikeLike