Mark Richardson —

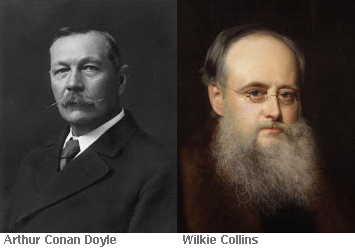

Edgar Allan Poe is generally regarded as the father of the detective fiction genre. In his classic stories, The Murders In the Rue Morgue, The Mystery of Marie Roget, and The Purloined Letter, Poe created the first mystery solving detective in literature, the inimitable C. Auguste Dupin. Poe was followed in short order by such unforgettable and still impressive mystery writers as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes stories and Wilkie Collins, whose best friend was Charles Dickens and whose masterful novels The Moonstone and The Woman In White elevated the genre to the level of worldwide acceptance. These authors and many others who soon arrived on the detective fiction scene all followed Poe in the structure of their works. For writers in this genre, Poe had laid down seventeen conventions for detective fiction.

These conventions laid out a structure for mystery stories which laid down a fair set of standards, allowing the reader to attempt to solve the crime along with the detective. They give the reader an opportunity to participate, as well as giving a recognizable format to such stories. They include the solving of a serious crime, usually murder, by the use of logic, observation and inference. The perpetrator must be introduced no later than a third of the way into the story—no pulling a previously unknown character out of nowhere as the book winds down. There must be several “red herrings” scattered throughout to confuse the issue. The detective usually has a right hand man who acts as the detective’s foil (Holmes’s Watson, Nero Wolfe’s Archie Goodwin, etc.). This foil, then, is able to present the reader with the thoughts of the detective, along with any criticisms or second-guessing. The Watsons often question the thinking of the detective (of course, in the end the detective’s rationale is shown to have been sound all along), and it is not uncommon for the detective’s partner to make a few clever but ultimately incorrect witticisms about the approach being taken by the crime solver. In addition to the “right-hand man,” there is often a bungling local constabulary or police officer. To keep the reader interested, there must be a large number of false suspects. When the detective has solved the mystery, he often gathers everyone around in the final chapter in order to fully disclose the solution at which he has arrived.

These conventions laid out a structure for mystery stories which laid down a fair set of standards, allowing the reader to attempt to solve the crime along with the detective. They give the reader an opportunity to participate, as well as giving a recognizable format to such stories. They include the solving of a serious crime, usually murder, by the use of logic, observation and inference. The perpetrator must be introduced no later than a third of the way into the story—no pulling a previously unknown character out of nowhere as the book winds down. There must be several “red herrings” scattered throughout to confuse the issue. The detective usually has a right hand man who acts as the detective’s foil (Holmes’s Watson, Nero Wolfe’s Archie Goodwin, etc.). This foil, then, is able to present the reader with the thoughts of the detective, along with any criticisms or second-guessing. The Watsons often question the thinking of the detective (of course, in the end the detective’s rationale is shown to have been sound all along), and it is not uncommon for the detective’s partner to make a few clever but ultimately incorrect witticisms about the approach being taken by the crime solver. In addition to the “right-hand man,” there is often a bungling local constabulary or police officer. To keep the reader interested, there must be a large number of false suspects. When the detective has solved the mystery, he often gathers everyone around in the final chapter in order to fully disclose the solution at which he has arrived.

In the early period of detective fiction, the detectives in these stories were largely cerebral men of mild manners who used their intellect alone to figure out whodunit. And then, along came Dashiell Hammett. He wrote of the conventional type of crime solver in his wonderful tale The Thin Man, which pitted the husband and wife team of Nick and Nora Charles and their helper, their little dog Asta, against the wiles of a clever murderer, but Hammett wanted to break away from some of Poe’s conventions while holding onto others. Hammett, a man’s man, wanted to create a tough-talking, tough-acting detective who stood up to the criminal in macho fashion and took a few hard knocks on his way to solving the crime. In his masterpiece, The Maltese Falcon, he created just such a fellow, private eye Sam Spade. Spade is hired to find an ancient sculpture, a black bird reputedly filled with treasures galore. In his hunt for the falcon, he encounters swindlers, dupes, a hit man and several murders, including that of his own partner, Miles Archer, whose murder the police suspect Sam committed himself (remember the bumbling police?). Spade is rendered unconscious, is beaten up, engages in gun play, and finds himself in one bad predicament after another—something the “Let’s sit here and think this thing through” detectives never encountered. Unlike the cerebral detectives of the past, Spade made do without the help of an assistant, something that would become a standard. The hard-boiled detectives; they are loners, who work without help. While it is common for the Watsons, Hastings, and Goodwins to narrate the stories, telling the reader of the deeds of Holmes, Poirot, and Wolfe, the hard-boiled detectives are their own storytellers, delivering the narrative in the first person.

Hammett also created another hard-boiled detective, who is the subject of two of his novels, The Dain Curse and Red Harvest (yes, as in a harvest of blood). He is also featured in a large collection of short stories aptly named after this detective, The Continental Op. The Op, so called because he is an operative for the Continental Detective Agency, is never called by any other name. We know him only as the Continental Op. He is, much like Sam Spade, the kind of guy who pokes around looking for trouble until he inevitably finds it, and in the process he uncovers the intricacies of the murders he has been assigned to solve. There is much more violence in the hard-boiled stories than in those which came before, and some of it is committed by the hero, something never really seen in the cerebral mystery solvers.

Hammett was followed by two more violent, brainy, determined hard-boiled ‘tecs, Philip Marlowe, created by Raymond Chandler and Lew Archer, Ross MacDonald’s detective. Marlowe appears in such classics as The Long Goodbye, The Big Sleep and Farewell, My Lovely. There were many other Marlowe novels, but these three are very representative of Chandler’s P.I. They all contain brutal murders, solved by the wise-cracking Marlowe as he winds his way through a series of plot twists and strange characters. Over time, Marlowe has become one of fiction’s best-loved crime solvers, and Chandler has taken his rightful place in the pantheon of mystery writers. Joining him on this list, but seemingly growing less and less prominent as the years go by is Ross MacDonald and his detective, Lew Archer. I don’t know why MacDonald’s popularity has diminished, because his stories are wonderful and his star, Archer, is clearly in the hard-boiled tradition of smart-mouthed, smart-brained private detectives. MacDonald’s best include The Big Chill (usually regarded as his magnum opus), The Drowning Pool, The Moving Target, The Way Some People Die, and Find A Victim. MacDonald was a prolific author, and speaking for myself, I have never been disappointed in any of them. Several of his books were turned into movies starring Paul Newman, who portrayed the detective, re-named “Lew Harper,” for the films.

One of the best of the more recent hard-boiled Private investigators is Robert B. Parker’s Spenser (with a second “S” like the great Elizabethan poet, Edmund Spenser). Spenser is a bit of an anomaly. He is an amateur boxer, a gourmet chef, a scholar, equally at home in a gymnasium or a library, and a crack shot with a pistol. He is also a man driven by his conscience to do the right thing, and at the same time, driven by his sense of justice to sometimes abandon his conscience. He is surrounded by a cast of recurring characters– his girlfriend Susan Silverman, a Harvard-trained psychoanalyst, his best friend Hawk, an African-American tough who could pass the entrance exam to any Ivy League school without studying for it, a gangster named Tony Marcus, who Spenser respects and who respects Spenser despite their existing on different sides of the law, a hit man named Vinnie Morris, who is a deadly foe to those he opposes but who owes his loyalty to Spenser, and police detective Martin Quince, who shares information with Spenser because he knows that despite his propensity for violence, Spenser will always be on the side of the police. Parker, who died just a few years ago wrote many Spenser novels. Among his best are The Godwulf Manuscript, God Save The Child, The Judas Goat, A Savage Place, The Widening Gyre, and Taming A Sea-Horse. But all of the Spenser novels are so good that one can’t go wrong no matter where he or she begins.

If you are a newcomer to crime fiction and don’t know where to start, choose any of the books mentioned above. Pick one up. Read it. Enjoy your new addiction, because that is what it will become. I recommend you don’t start your journey through the hard-boiled detectives with Parker. Start with Hammett. Move on through Chandler and MacDonald. Watch the development of the genre from one of these classic authors to the next. You’ll see patterns, and deviations from the pattern. And you’ll experience an unexpected pleasure in the world of crime.

Very cool post. I am a huge fan of detective TV shows, such as Columbo, Poirot and Marple (TV versions), Father Brown, Midsommer Murders, etc, but have hardly read any mystery novels. This gives me some good ideas for starting points!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much. I hope you enjoy the books as much as you do the shows.

LikeLike

Wonderful post! Raymond Chandler is one of my favorite writers. Once I read “The Big Sleep” I had to read all the rest. Have you ever read the 87th precinct police procedural novels by Ed McBain (pen name of Evan Hunter)? They perhaps lack the literary qualities of many of your examples, but are quite enjoyable. BTW, did you know that ‘Archer’ was switched to ‘Harper’ because Paul Newman had a string of successes playing characters whose names began with ‘H’ and didn’t want to jinx himself?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your nice comment. I have not read McBain, but I will give him a shot. And I did not know that this was the reason for the name change from Archer to Harper. I thought it was some director’s idea. LOL. Thanks for the information.

LikeLike

I certainly enjoy reading detective crime fiction. After reading quite a few novels in this genre over the past few years, my definite plot favorite is found in “The Devotion of Suspect X” by Keigo Higashino. Has anyone else read this book? If not, I highly recommend it. Unlike most crime fiction novels, I found myself rooting for the criminal. And the plot development was a jaw dropper. I was totally caught off-guard toward the end of the novel. I have read two other novels by Higashino. They are also quite good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mark, a double-barrelled “smoking gun” question for you:

1) With your naturally inquisitive mind, after you initially got into detective stories, at what point did you make a concerted effort to analyze varying styles of literary construction with the “premeditated” intent of identifying whodunit? Which authors kept you guessing longest & which did you develop a knack for figuring out the mystery?

2) In your professional career doing investigations with Rock County, did you find a “carryover effect” in “real life” situations & circumstances?

(Maybe you could develop all this into an essay in itself? Would be interesting . . . )

LikeLike

The answer to your first question, Bob, is easy for me to answer. I had only dabbled in detective fiction, reading lots of Agatha Christie and really no other mystery writers, until, as a young man, I took a special studies English course called “Classics of Detective Fiction” at UW-Whitewater under Dr. Margot Peters. Her intent was to differentiate between the great writers of the genre and the many, many lesser writers. She drove home the point that the reader had NOT solved the mystery merely by guessing correctly whodunit. He/she must actually SOLVE the mystery in order to make that claim. One had to figure out the whole of the circumstances. The truth is that, when looked at in this vein, they ALL kept me guessing, and still do. I seldom figure out all of the aspects of the mystery, even if I do correctly deduce the perpetrator.

As for your second question, there was never any real connection between literature and life in the solving of crimes, but one thing DID always stick with me—Philip Marlowe’s statement that “99.99% of the time, the truth makes sense. If it doesn’t make sense, you’re not hearing the truth.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Although he is not a private eye or hard boiled. Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache, a wise and cunning Montreal homicide investigator, is a compelling character. I am currently reading Penny’s twelfth book in her mystery series.

LikeLiked by 2 people