Mark Richardson —

Baseball is played very differently today than when I was young. There has been a revolution going on for several years that has fundamentally changed the way players and managers approach the game, how it is taught, and how fans watch it. The changes began around the year 2000, when a group of devoted baseball fans had, some years previously, formed a group which called itself The Society for American Baseball Research, or SABR. It began as a casual online meeting place for hardcore baseball aficionados to gather and discuss their favorite pastime. But, as any true fan can attest, opinions shared must be challenged, and tested, and verified. So, it wasn’t long until discussions of strategy became matters of great debate over effectiveness.

Baseball is played very differently today than when I was young. There has been a revolution going on for several years that has fundamentally changed the way players and managers approach the game, how it is taught, and how fans watch it. The changes began around the year 2000, when a group of devoted baseball fans had, some years previously, formed a group which called itself The Society for American Baseball Research, or SABR. It began as a casual online meeting place for hardcore baseball aficionados to gather and discuss their favorite pastime. But, as any true fan can attest, opinions shared must be challenged, and tested, and verified. So, it wasn’t long until discussions of strategy became matters of great debate over effectiveness.

As the SABR membership grew, opportunities were discovered to test some of these theories in a concrete manner. As more and more members brought real analytical skills to the group, it was decided that the game’s history should be taken apart, piece by piece, and examined under a microscope. So, a group of over 100 members, all of whom when not arguing about baseball, were employed in various occupations in which the study of numbers was the most significant element, assigned themselves a gargantuan task. Thus mathematicians, CPA’s, statisticians, and so on took on the job of breaking down the history of baseball, game by game, to determine what strategies had proven successful and which, throughout the years, had not.

To this end, they split the work evenly among themselves, some taking this 20 year period and others that period, and still others yet another 20 year segment of time, and each, then, pouring over newspaper accounts of every game, or at least nearly every game played in the major leagues from the their origin in 1871 to the time of the study. After many grueling years of analysis, the information assembled entailed many thousands of games, and the results yielded many shocking facts. Things that even the most astute baseball fans believed to be unshakably established as facts about the game were found to be false, and things deemed unimportant were suddenly seen as the most significant of all. For instance, the bunt, long regarded as a very necessary offensive tool, was discovered to have nearly no effect on scoring at all. The hit and run play, in which a base runner takes off for the next base while the batter swings at the pitch that is delivered, almost regardless of the pitch location, and the stolen base, were found to be far more devastating when unsuccessful than had been previously supposed. Batting average, for well over a century regarded as the best measure of how good a hitter a player was, was revealed to be anything but that. And new measures such as OPS (the combination of a batter’s on-base percentage and his slugging average), WAR (wins above replacement), and RISP (batting average with runners in scoring position) were revealed to be the statistics which measured a player’s true worth. These new statistics were originally called SABRmetrics, after the people who had brought them to prominence, but have in recent years been called the new analytics.

To this end, they split the work evenly among themselves, some taking this 20 year period and others that period, and still others yet another 20 year segment of time, and each, then, pouring over newspaper accounts of every game, or at least nearly every game played in the major leagues from the their origin in 1871 to the time of the study. After many grueling years of analysis, the information assembled entailed many thousands of games, and the results yielded many shocking facts. Things that even the most astute baseball fans believed to be unshakably established as facts about the game were found to be false, and things deemed unimportant were suddenly seen as the most significant of all. For instance, the bunt, long regarded as a very necessary offensive tool, was discovered to have nearly no effect on scoring at all. The hit and run play, in which a base runner takes off for the next base while the batter swings at the pitch that is delivered, almost regardless of the pitch location, and the stolen base, were found to be far more devastating when unsuccessful than had been previously supposed. Batting average, for well over a century regarded as the best measure of how good a hitter a player was, was revealed to be anything but that. And new measures such as OPS (the combination of a batter’s on-base percentage and his slugging average), WAR (wins above replacement), and RISP (batting average with runners in scoring position) were revealed to be the statistics which measured a player’s true worth. These new statistics were originally called SABRmetrics, after the people who had brought them to prominence, but have in recent years been called the new analytics.

* * *’

The first team to embrace the new analytics was the Oakland A’s, under the direction of General Manager Billy Beane. Beane’s story was told in Michael Lewis’s 2004 bestseller, Moneyball, which was made into a feature film starring Brad Pitt as Beane. Lewis portrayed Beane, probably accurately, as a visionary who embraced the concept of emphasizing statistical analysis as a revolutionary new way to approach the game. Beane himself, though, looked at it in a bit of a different light. He regarded himself as a desperate front office man confronted with the problem of putting a winning team on the field without a payroll large enough to do so in the traditional manner.

Beane began searching the waiver wires, the Rule 15 draft options (those players under contract to another team but left unprotected by being omitted from the team’s 40 man roster), and other bargain basement methods of obtaining players whose skills had been unappreciated or undervalued by their previous teams. His search was focused on those players who had a history of reaching base successfully, of scoring runs, of completing plate appearances without making outs. This last component is vital to the understanding of the new SABRmetrric measures. Every batter who goes to the plate and does not make an out has contributed to the continuation of the inning, thus increasing the opportunity for run scoring. A successful at bat does not mean hitting a home run or getting a base hit; it means not making an out. Every out puts an offense closer to the end of the inning, so avoiding outs is the single most important outcome of every plate appearance.

Beane secured as many players as possible with high on-base percentages and slugging averages (a measure of the player’s ability to get extra base hits), and his success (the A’s reached the playoffs five times in six seasons with the roster of players who had been regarded as expendable by other teams) led other GMs, most notably Theo Epstein of the Boston Red Sox to follow his example. Epstein was the youngest General Manager in major league history, and he was eager to embrace the new analytics and Beane’s way of thinking. His success in Boston was to culminate in the first World Series title for the Red Sox in 86 seasons.

* * *

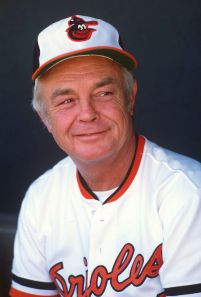

The new analytics have wreaked havoc on us old timers who loved the game that we are now told was played ineffectively for 150 years. I was, in fact, on board with the uselessness of the sacrifice bunt from a very early age. This play, of course, is one in which the batters bunts, or softly deadens the ball as it is pitched to him, in order to give himself up so that the base runner(s) might safely advance to the next base. After watching baseball with a dedication bordering on obsession for a few years as a child, I told my friend Rick Wyman that there was nothing more stupid than a sacrifice bunt. “It never works,” I told him. All they ever get from it is an easy out.” Rick thought I was crazy. Why would managers, who had been around baseball all their lives, employ a strategy that didn’t work? When I was about 12 or 13 years old, the Baltimore Orioles hired Earl Weaver to manage the team. Weaver was in fact the first true progenitor of the SABRmetricians who would change the game decades later. He recorded the results of every play on index cards, which he then carried in his back pocket. By season’s end it looked like he was toting the Encyclopedia Britannica around in his pants. He was also the first manager to utilize computers to sort his information. One day the Orioles were playing in the Saturday Game of the Week, and broadcaster Tony Kubek interviewed Weaver before the game began, and he asked Weaver why he never used the sacrifice bunt, which was so dear to other managers. Weaver said, “Because there’s nothing more stupid than making an out on purpose. We only get 27 outs a game. Why would we want make any of them on purpose?” I felt absolutely vindicated. I couldn’t wait to tell the unbeliever Rick Wyman what Weaver had said. Rick was singularly unimpressed. He could care less what crusty, white-haired old Earl had to say. In Rick’s mind, Weaver didn’t even have the good sense to be a member of the Chicago Cubs organization, so what could it matter what he thought about anything? Now, of course, thanks to the tireless work of the SABR crew, we know that the sacrifice bunt is indeed both futile and foolish. We know that a team has a better chance, in fact a MUCH better chance, of scoring a run in an inning in which they have a runner on first base with nobody out than they have of scoring when they have a runner at second with one out. We didn’t know the numbers back in the 1960s, but some of us knew that the bunt was just plain dumb.

There are now also new and complex ways to determine an individual player’s contribution to his team’s victories. We used to think that batting average was one of these contributions. But the new analytics tell us otherwise. We are all impressed by batters who hit for an average above .300. That has always been the measure of greatness. The odds are so stacked against the hitter in a game in which the pitcher always knows which of four or five pitches he going to throw while the batter can only try to guess what to expect, and in which the pitcher has eight teammates scattered about the diamond to help him retire the batter, while the hitter has to go it alone. This being the case, a batter who successfully hits safely in seven out of ten at-bats is a great hitter. But does this equate to a solid contribution to wins? The new analytics say, “maybe not.” If all a hitter does is hit, he is not going to reach base often enough to make a real contribution. Because, while a .300 batting average is excellent, a .300 on-base percentage is abysmal. In order to be considered an effective hitter, a player must find other ways of reaching base safely. The most common way, of course, is by drawing walks. There has been a saying in baseball for as long as there has been baseball, which goes, “A walk is as good as a hit,” but nobody ever really believed it. Turns out it is absolutely true. It stands to reason; the more base runners a team gets, the more opportunities it has to score. But OBP itself is not enough, either. In order to be a real contributor to victories, a hitter must compile a stout OPS. The OPS is the combination of on-base percentage and slugging average. The slugging average is determined by dividing the number of at-bats by the number of extra base hits (doubles, triples, and home runs). This is the measure of a batter’s power, or the success he has in putting himself in scoring position. So if a hitter has a batting average of .324 and an OBP of .482, his OPS is .806, and his team can thank him for a stellar contribution to wins.

The new analytics have taught general managers just what types of players they should be seeking, what skills translate to winning baseball, and what skills that used to be valued should actually be avoided. They tell managers what strategies to employ and what player match-ups make the most sense. They tell pitchers, hitters, and base runners what methods of attack make the most sense. But, have the changes that these new ways of looking at what works and what doesn’t work take more away from the game than they have brought to it? I would argue that they have. The shifts that defenses employ, wherein they stack all the infielders on one side of the diamond when they have determined that a batter is most likely to hit the ball to that side, the limits on the number of pitches a pitcher is allowed to throw, the near-absence of the stolen base and the hit and run, two of the game’s most exciting plays prior to their extinction, all coupled with the new rules prohibiting contact with catchers and infielders by base runners, have all diminished the game by degrees. The focus on slugging average has resulted in a new phenomenon, the launch angle, as players study the angle of their swing to determine which is the most optimal to the generation of power. This lust for greater power, in turn, has exponentially increased the number of strikeouts. Every year for the past 12 seasons there has been a new record set for the number of hitters striking out. And coinciding with this, the number of home runs have seen new records, surpassing even the astronomical totals of the steroid era. In an average game these days, far more pitches are not put into play than are as the game has devolved into a game of strikeouts, walks, and home runs.

The new analytics have taught general managers just what types of players they should be seeking, what skills translate to winning baseball, and what skills that used to be valued should actually be avoided. They tell managers what strategies to employ and what player match-ups make the most sense. They tell pitchers, hitters, and base runners what methods of attack make the most sense. But, have the changes that these new ways of looking at what works and what doesn’t work take more away from the game than they have brought to it? I would argue that they have. The shifts that defenses employ, wherein they stack all the infielders on one side of the diamond when they have determined that a batter is most likely to hit the ball to that side, the limits on the number of pitches a pitcher is allowed to throw, the near-absence of the stolen base and the hit and run, two of the game’s most exciting plays prior to their extinction, all coupled with the new rules prohibiting contact with catchers and infielders by base runners, have all diminished the game by degrees. The focus on slugging average has resulted in a new phenomenon, the launch angle, as players study the angle of their swing to determine which is the most optimal to the generation of power. This lust for greater power, in turn, has exponentially increased the number of strikeouts. Every year for the past 12 seasons there has been a new record set for the number of hitters striking out. And coinciding with this, the number of home runs have seen new records, surpassing even the astronomical totals of the steroid era. In an average game these days, far more pitches are not put into play than are as the game has devolved into a game of strikeouts, walks, and home runs.

Much of the excitement that I knew the game to possess when I was young is gone. I don’t think baseball is ever going back to the game I knew, and I lament the loss. But I still love baseball, still watch it on TV and listen to it on the radio, and still read and write about it. It is in my blood and it always will be. So as a new generation makes it’s mark upon the game, and one more old codger moans and groans about the loss of “real” baseball, it comes into my mind that when I was ten I laughed at the old men who said the things I’m saying now. Things change, but somehow, they wind up the same.

This is terrific stuff Mark.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I too bemoan most of the changes to the game, especially the strikeouts and walks, but even the home runs, because all of these things degrades the value of good fielding. I also don’t like the fielding shifts, which is because few players can hit to the opposite field against today’s pitchers. It must be hard trying to hit to the opposite field against a 99MPH fast ball. I wish we could create a speed limit on pitches, but obviously we can’t.

In spite of what Earl Weaver said, there have been some teams in the past who won championships by playing “small ball”. One of the starkest was the 1962 season, the year that the Dodgers lost to the Giants in a 3-game playoff and the Giants then lost to the Yankees in a Game 7. That year the Dodgers’ pitching was only marginally better than the Giants and Yankees, but hitting-wise the Dodgers were a unique team. They hit 64 fewer home runs than the Giants and 59 fewer home runs than the Yankees. Maury Wills won the NL MVP with an outstanding OPS of .762 and a remarkable 759 plate appearances. Of course, he is more remembered for stealing 104 bases. But, it helped that his teammate, Tommy Davis, had 230 hits and drove in 153 runs. Even still, Willie Mays hit 49 home runs and drove in a not-too-shabby 141 runs, while his OPS was a mere 0.615. Who wouldn’t have chosen Willie Mays over Maury Wills or Tommy Davis for their team? Nevertheless the Yankees won Game 7 of the WS by a score of 1-0 in a game that was remarkable for there being no RBIs. The only run was scored on a double play. The Yankees had no extra base hits while Mays hit a double and McCovey hit a triple. Ralph Terry struck out only 4 Giants. But, the most salient statistic of the game is that Terry walked nobody in 9 innings. That’s the kind of pitching that I miss.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly small ball has had its successes over the years. Nonetheless, a study of the outcomes does prove that, in general, the sacrifice bunt is a self-defeating strategy due to the prominence of its failures to result in a run scored.

LikeLike

Thanks very much.

LikeLike

As my friend Tim McKearn pointed out to me after reading this, a guy who gets hits seven out of ten times would be a pretty darn good hitter. I meant, of course, three out of ten times.

LikeLike

I should point out that baseball’s leading SABRmetrician, Bill James, who abhors the sacrifice bunt as much as did Weaver, does address one instance in which the sacrifice does make sense and is successful many, many more times than is ordinarily the case. That is in the instance of a tied or one run ballgame that has gone past the seventh inning, with a runner on second base and no outs. Moving the runner from second to third can result in the batter driving in a crucial run in any number of ways. But, as for moving a runner from first to second via the bunt, James is adamant about the foolishness of such a move. And he claims that bunting the runner from second to third any earlier than the 8th inning is equally unproductive of wins.

LikeLike

Excellent, Mark! You make things clear for the layman, as well as bringing out all the esoteric stats & strategies rabid fans so love; this is difficult to accomplish, but you have done it so well!

A couple questions about the prominence of the shift and the new upcoming rules about mandatory batters-faced by relievers. Do you see more batters adjusting to extreme shifts and either singling to the undefended area or dropping down a bunt in the open space? This would seem to be an effective way of getting on base, executing the SABRmetrics emphasis. And, do you think the elimination of one-batter relievers for matchups will improve the game? As you know so much about baseball & have sound judgment, I look forward to seeing your thoughts.

(P.S. — Just for the record, in ’62, Willie Mays’ SLUGGING was .615. This, added to his OBP of .384 yields an OPB+SLG of .999 — rarified air! He also scored 130 runs & drove in 141, plus playing his usual superlative defense in center field — absolutely great.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Bob. In answer to your question, I think that if batters were going to try to beat the shift by bunting to the open area we would have seen this by now. The shifts have been going on for several years now with only a very minimal number of hitters attempting this. They seem to feel, much like Ted Williams did in his day, that their success is going to lie in taking their normal approach.It would seem to make sense that they alter their methods to take advantage of the side of the diamond that is being given to them, but we just haven’t seen it to this point. I think that the new pitching rule puts the defense at a tremendous disadvantage. There are many, many better ways to speed up the game, in my opinion, and I think that this may be a one or two year rule that is revisited and eliminated rather quickly.

LikeLike