Bob Bates —

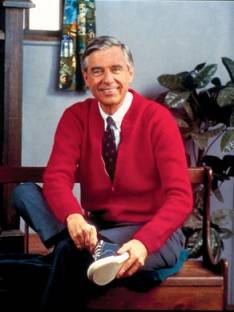

The brown wooden door opens and Mister Rogers enters, looking directly into the camera. Stepping over to the closet, he slips out of his jacket, hangs it up, and dons his zip-up cardigan (always knitted by his mother). He casually sits down to flip off his loafers and put on his blue canvas deck shoes—all while liltingly singing “It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood,” asking us to be his neighbor for an hour on PBS.

If we aren’t already familiar with this iconic scene on our home television sets, we can drop in at our local theater and see it on the Big Screen. In the recently released, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Tom Hanks assumes the character of Fred Rogers on a re-creation of the 31-years-running WQED TV studio set in Pittsburgh. This film follows the well-received feature-length documentary, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor,” which was released in 2018.

The new movie starring Hanks is told from the cinematic perspective of real life cynical Esquire Magazine journalist Tom Junod, based on his assigned interview experience in 1998 with Rogers. Junod, played by Matthew Rhys (best known for his role as Phillip Jennings in The Americans), is fictionalized in the character of Lloyd Vogel.

Reviews of A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood have been overwhelmingly positive. New York Times film critic A. O. Scott terms Mister Rogers’s empathic decency as “what we now [would] call his emotional intelligence.” Ann Hornaday, movie reviewer for the Washington Post, writes, “In an era that seems fatally mired in fear, anger, and mistrust [the movie] feels like an answered prayer.” Stephanie Zacharek of Time says, “It’s one of those movies you didn’t know you needed.” She refers to the Neighborhood set as “Mister Rogers’ safe house,” and points out that rather than a biopic of Fred Rogers, the cinematic version focuses in large part on how Fred entices the wounded Junod character to call up emotions buried inside himself regarding his inner incapacity to come to terms with the estranged relationship he has had with his father and now, as a new father himself, how to adequately approach fatherhood. The theater audience is surreptitiously invited into “therapy sessions” illustrating Fred’s ability to gently but penetratingly interrelate with and help heal adults as well as children. In this way, the film speaks to the enduring impact of Mister Rogers on American culture.

On the Big Screen as well as on television and in real life, Fred might humbly comment, “who you see is the real me.” As family, friends, cast members, Junod, and the universe of neighbors came to realize, there was nothing phony about Fred Rogers.

* * *

Maxwell King’s 2018 book, The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers, delivers a comprehensive assemblage of biography, events, influences, and observer accounts that reveal the environment and experiences that shaped Fred in real life and contributed to the reality-and-imagination television Mister Rogers.

Fred McFeely Rogers, the only child of James Rogers and Nancy McFeely Rogers, was born on March 20, 1928, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. When Fred was 11, his parents adopted a daughter—a “sister” for their son. A density of polluting factories in the Pittsburgh region, including Latrobe about 40 miles southeast, made the air hazardous to breathe. Young Fred suffered from childhood asthma, and the entire summer of his tenth year he spent bed-confined with a similarly afflicted neighborhood 16-year-old boy in a small room equipped with the first air conditioner to arrive in Latrobe. As he approached adolescence his asthma improved, and thereafter his health was basically normal, permitting a full range of activities.

As a preadolescent he was chubby, and school kids would taunt him as “Fat Freddy,” occasionally chasing him on his route home. During his adolescent teenage years, he became lean and athletic-looking, participating in swimming and tennis. Subsequently, throughout his adulthood he maintained a routine of early morning swim workouts at the Pittsburgh Athletic Association (where his locker has been memorialized with a plaque). He attributes his life-long fitness and steady weight of 143 pounds to this enduring routine. Fred liked to point this out, and on occasion would recount to his viewers that one equals “I,” four equals “love,” and three equals “you.” With his gaze penetrating the studio camera while bringing his presence into millions of TV homes, he would delightedly and charmingly affirm,”I — love — you!”

Both Jim Rogers and Nancy McFeely came from very wealthy families, and Fred was exposed early in childhood to reading, music, the arts, puppetry, and religion. At age four he would sit beside his mother in a front pew of the Latrobe Presbyterian Church, reverently observing and carefully listening, often posing questions about what puzzled him. His mother was active both in the church and wider community, especially at the hospital, where she volunteered long hours to needed services; she also freely gave of her wealth to many in need—money, gifts, and visits. It is evident from this background that Fred internalized such generous role modeling.

While in elementary school and struggling to fit in with his peers, Fred found refuge in music and puppetry. In the family attic he set up his own puppet theater, performing alone or on occasion before family and invited friends, expressing his imagination and often playing miniature piano in accompaniment.

At age 10, already an accomplished, enthusiastic pianist, Fred was promised by his maternal grandmother that he could select his own personal piano for home practice. He took this to heart and promptly marched downtown, alone, to sample pianos at the expansive Latrobe music store. He chose a second-hand 1920 Steinway Concert Grand (nine feet long, weighing about 1000 pounds). Once restored, it has always been kept in immaculate condition over the decades, now on display at Pittsburgh’s Fred Rogers Center, which is dedicated to addressing children’s developmental needs.

In high school, Fred was active and popular, becoming student council president, yearbook editor, accomplished in oratory competitions, acting in school theatrical productions, and academically excelling and being inducted into the National Honor Society. Upon graduating, Fred was accepted at Ivy League Dartmouth, but found it unfulfilling, and after two years he transferred to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, which had a top flight music program.

Fred met the woman who would become his wife, Joanne Byrd, at Rollins College. She was already an accomplished concert pianist, while Fred became a music major with a special interest in composing. They married in July 1952 and eventually had two children, Jim and John.

The newly married couple relocated to New York City, where Fred had accepted a job in fledgling public television’s early attempts at producing programming that focused on children’s educational needs. His strong interest in education and developmental psychology led to a series of moves: New York for two years, Pittsburgh for five, Toronto’s public Canadian Broadcasting Corporation for three, and then back to Pittsburgh’s WQED for the rest of his career, with 31 years at the Mister Rogers Neighborhood studio.

During the 1950s to early 1960s, in addition to long hours on the set, writing the scripts, composing the music, and directing the shows, Fred studied at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, receiving his Master of Divinity degree in 1963. As an ordained Presbyterian minister, he resisted traditional assignments, preferring to engage in pastoral work through puppets rather than pulpits. Beyond stressing educational elements, he saw puppetry as a direct appeal to children’s imagination and open-ended involvement in their world; every show featured a trip to the Neighborhood-of-Make-Believe.

During this time, Fred met Dr. Margaret McFarland, a child and family psychologist of national repute, with whom he collaborated for three decades. The two of them consulted multiple times weekly, discussing, outlining, and crafting daily and weekly scripts that addressed an array of issues important to children and their family’s well being. A high priority with Fred was always self-acceptance, dignity, self-discipline, and developing respect for others. He found Dr. McFarland’s input inestimably valuable in achieving these programming aims.

Fred did not appear on camera for the first two years of his involvement in children’s programming, preferring instead to operate out-of-sight as a puppeteer. It was at this time that his blue sneakers became a trademark, as he needed to scoot from one behind-the-scenes set location to the next without producing footfalls on the audio.

Throughout his career, as biographer Maxwell King notes, Fred was committed to “helping young children find and evolve their own capacities, including that of self-discipline, because he believed it would make them stronger adults.” In these approaches, Fred was addressing both the individual child of the moment, yet planting seeds and introducing tools for these children to grow and mature into well-integrated adults. One principle he adhered to in every production was to forbid any advertising directed at children, considering this to be a form of moral exploitation. Fred also stressed the importance of reading, stating, “The white spaces between the words are more important than the text, because they give you time to think about what you’ve read.” Uncounted observers of how Fred operated over nearly a half-century noted his modeling of cherishing and cultivating listening, silence and reflection, and just plain slowing down the pace of your world.

Fred inherited the practical, strong faith of his mother. When events of the world brought cruelty, destruction, tragedy, and suffering to our attention through media coverage, her calming advice was, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping … there are so many caring people in this world.”

King writes that from the Presbyterian values practiced by his mother, Fred learned the importance of “hard work, responsibility and caring for others, parsimony, duty to family, ethical clarity, a strong sense of mission, and a relentless sense of service to God. … Though an artist at heart—writing scripts, operas, musical scores, creating puppets and tales of fantasy—he could never escape a life of duty. The miracle is that he so wonderfully, successfully put the two together.” Yet, on air, Fred never brought up God or religion, speaking to the heart of humanity a reverence for all of life.

In the 1998 Esquire profile by Tom Junod, a “self-described ‘bad boy’ journalist who cultivated a reputation for controversy,” Junod wrote about his initial skepticism of Fred’s apparent lack of pretentiousness. However, during his interviews he came to see that Fred was an “authentic person in every setting. … His ability to draw a person in on his own terms was an incredibly powerful thing … spiritually powerful, but he was also interpersonally powerful,” with an “absolute trust in fully engaging others, a fearless authenticity.”

Besides his own public television show, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, Fred contributed to the strengthening of public television more generally during its early, struggling years. His genuineness and persuasive power were highlighted in his testimony before the 1969 Senate Subcommittee on Communications, chaired by Republican “tough guy” John Pastore of Rhode Island. President Richard Nixon wanted to quash the federal funding necessary for establishing the proposed Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and a brusque Senator Pastore was just the guy to carry out such intentions. However, Fred, almost single handedly secured the necessary funding through his low-key spontaneous presentation.

Fred arrived at the hearings with a prepared statement emphasizing the important contributions public television could make to America. But, in seeing Pastore brush off others’ advocative testimony, he asked if it would be okay to simply express himself spontaneously. With Pastore’s nod, Fred began:

This is what I give. I give an expression of care everyday to every child, to help him realize that he is unique. I end the program by saying, “You’ve made this day a special day by just your being you. There’s no person in the whole world like you, and I like you just the way you are.” I feel that if we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service.

After a long pause, Pastore said, “I’m supposed to be a pretty tough guy [but] I’ve got goosebumps.”

Fred continued, making a calmly impassioned plea for a forum addressing America’s children, especially those on the margins of society. He called attention to the current state of “bad television,” stressing the need for thoughtful, positively affirming public programming that would contribute to what “helps us become what we can.” A visibly moved Pastore solemnly responded, “I think it’s wonderful. That is so wonderful! Looks like you just won the twenty million dollars.”

* * *

Fred Rogers’s favorite quotation, which he kept framed near his office desk, was from The Little Prince by French author and war hero pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupery: “Now here is my secret, a very simple secret. It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

Maxwell King writes that Fred applied this with the “profound conviction that what’s on the surface—the everyday pain and frustration and small joys of life—is not what is essential. The essential is to be found in depth and introspection, in searching for meaning, and then finding the truth that comes from that meaning.” Fred felt that one’s emotions and feelings needed to be turned into understandings that could provide comfort, self-esteem, self-discipline, and personal strength. This was always at the core of the everyday experience children gained from the Neighborhood.

When asked what it is like to be a celebrity, Fred responded:

I don’t think of myself as somebody who’s famous. I’m just a neighbor who comes and visits children. I happen to be on television. But I’ve always been myself. I never took a course in acting. I just figured that the best gift you could offer anybody is your honest self … and thankfulness for accepting me exactly as I am … [always stressing] You are special because nobody in the world is exactly like you.

To Tom Junod, he advised, “The connections we make in the course of life, maybe that’s what heaven is, Tom. We make so many connections here on Earth. … It is so important to have people we love beside us when we have to do difficult things in life.”

Ann Hollingsworth, in her 2005 book, The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers, quotes Fred’s response to the issue of the meaning of our lives.

Each one of us is such a little part of life . . . [yet] a wonderful part, a sad part, a joyous part. … Each part can make an enormous difference in the lives of others, especially when we commit to a life of spiritual wholeness that is represented by looking inward with our hearts, looking outward with our eyes—how we see others affects how we treat others—and applying what we’ve learned practically.

Fred’s personal theology was that “there is sacredness in all creation and each one of us is to be valued and appreciated.” This was at the heart of the Neighborhood and the basis for each Beautiful Day.

Fred was diagnosed with advanced metastatic stomach cancer in October of 2002 and died four months later, on February 27, 2003, just short of 75 years old. Tim Lybarger, Neighborhood Archive website founder, believes that Rogers’s work is as relevant as ever today: “Who isn’t starving for a message of self-value and peace and love and appreciation?”

Addendum: Songs By Mr. Rogers

Its a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood: A beautiful day for a neighbor / Would you be mine / Could you be mine? … I’ve always wanted to have a neighbor just like you / I’ve always wanted to live in a neighborhood with you / So let’s make the best of a beautiful day / Since we’re together we might as well say / Would you be mine? / Could you be mine? / Won’t you please? / Won’t you please? / Please won’t you be my neighbor?

It’s You I Like: It’s not the things you wear / It’s not the way you do your hair / But it’s you I like / The way you are right now / the way down-deep inside you / Not the things that hide you / Not your toys, they’re just beside you / But it’s you I like / Every part of you / your skin, your eyes, your feelings / whether old or new / I hope that you’ll remember / even when you’re feeling blue / that it’s you I like / it’s you yourself / It’s you, it’s you I like.

I’m Proud of You: I’m proud of you / I hope you’re just as proud as I am proud of you / I’m proud of you and I hope that you are proud / … And that you are learning how important you are / how important each person you see can be / Discovering each one’s specialty is the most important learning / … I’m proud of you and I hope that you are proud of you, too!

You’re Growing: You used to creep and crawl real well / but then you learned to walk real well / There was a time you’d coo and cry / but you learned to talk and, my! / You almost always do your best / I like the way you’re growing up / It’s fun, that’s all ! / You’re growing, you’re growing, you’re growing in and out / … you’re growing all about / Your hands are getting bigger now / your arms and legs are longer now / you even sense your insides grow / When Mom and Dad refuse you, you’re learning how to wait now / It’s great to hope and wait somehow / I like the way you’re growing up / It’s fun, that’s all! / Someday you’ll be grown up, too / and have some children grow up, too / Then you can love them in and out and tell them stories all about / the times when you found great surprise in growing up / And they will sing It’s fun, that’s all!

What Do You Do with the Mad that you Feel? : What do you do with the mad that you feel / when you feel so mad you could bite? / When the whole wide world seems oh, so wrong / and nothing you do seems very right? / What do you do? Do you punch a bag? / Do you pound some clay or some dough? / Do you round up friends for a game of tag / or see how fast you can go? / It’s great to be able to stop when you’ve planned a thing that is wrong / And able to do something else instead, and think this song: / “I can stop when I want to, can stop when I wish / I can stop, stop, stop any time / and what a good feeling to feel like this / and know the feeling is really mine!” / Know the feeling that there’s something deep inside / that helps us become what we can / For a girl can be someday a lady / and a boy can be someday a man.

Hi Bob. I just want to say that I appreciate you writing this piece on Fred Rogers. In an age where vitriol and polarization seem to dominate our lives, it is good to be reminded that people like Fred Rogers have a different message. I confess that as a parent of a young child I did not pay much attention to Mr. Rogers. But that was my failing, not his. I wish there were more people like him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, there are so many positive qualities Fred Rogers genuinely and consistently exibited, both on the air and in public and private settings. Also remarkable in an era of widespread discrepancies in material wealth and, consequently, systemic basic human needs not being adequately addressed, is his background of coming from family wealth and privilege yet being humble and displaying service to human and community needs.

Fred Rogers’ legacy stands out because there are so relatively few prominent public figures who commit to long term devotion to such worthwhile priorities as education, personal and character growth, and sociopsychological health and modeling. His mother emphasized selfless servanthood and pitching in when needs present themselves. She also stressed, in times of turmoil and tragedy to “look for the helpers.” Among us are millions of unsung helpers in ways small and seemingly insignificant, but it is arguably they who sustain the everyday fabric of goodness in our world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Bob, I like your piece. It was very informative and entertaining. As a kid I watched Mr. Rogers on TV. My favorite part was when he sang while putting on his shoes and sweater. I did not like the land of make believe. I think it was because I was never a puppet fan. I used to wish the train would break down before it got there, but it never did. I was however a fan of Fred’s. He was so nice. He always made me feel happy. Maybe even a little special. Like he was talking directly to me. The world could use another Fred or three.

LikeLike